What do trademarks such as Intel, Red Bull, Visa, Hermès or Rolex have in common? They have all been recognized as trademarks with a reputation in most EU countries. As a general rule, a trademark’s reputation affords reinforced protection from third parties attempting to register identical or similar signs. However, reputation is not always relevant. This has been made quite clear in the CJEU judgment of 11 June 2020, in case C-115/19, which concludes that when making a comparison of the similarities and differences between two trademarks, reputation is not a factor to be considered. Nevertheless, the impact that the trademark’s reputation will have when analyzing the likelihood of confusion is quite another matter. Let’s take a look.

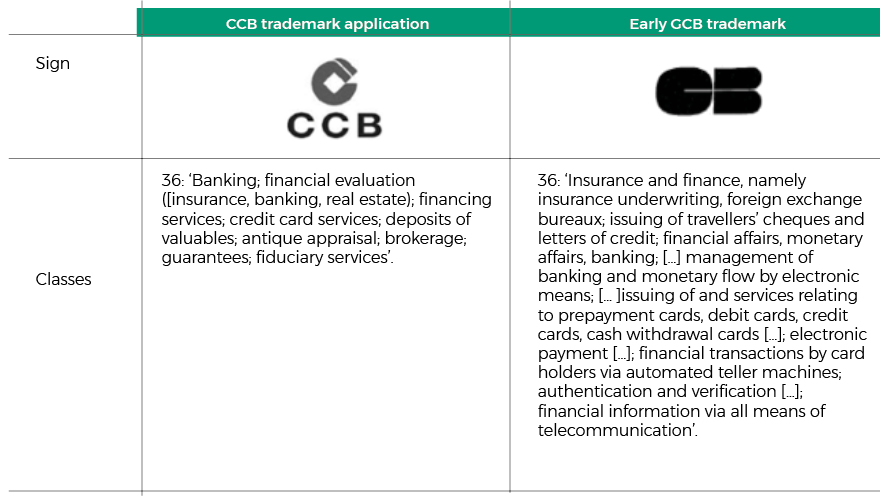

The conflict arose when China Construction Bank (CCB) filed a European Union Trademark application, as reproduced below, and its registration was opposed by the Groupement des cartes bancaires (GCB) based on one of its earlier marks,

GCB’s opposition to the CCB trademark application was based on two different premises, pursuant to articles 8.1(b) and 8.5 respectively, of The Regulation on the European Union Trademark. In the first case, due to the likelihood of confusion according to which, trademark registration should be refused when:

“because of its identity with, or similarity to, the earlier trade mark and the identity or similarity of the goods or services covered by the trademarks, there exists a likelihood of confusion on the part of the public in the territory in which the earlier trade mark is protected; the likelihood of confusion includes the likelihood of association with the earlier trade mark”.

In the second case, taking unfair advantage of another trademark’s reputation or being detrimental to its distinctive character which occurs where the trademark application:

“is identical with, or similar to, an earlier trade mark, irrespective of whether the goods or services for which it is applied are identical with, similar to or not similar to those for which the earlier trade mark [of the Union] is registered, where, in the case of an earlier [EU ]trade mark, the trade mark has a reputation in the [Union] or, in the case of an earlier national trade mark, the trade mark has a reputation in the Member State concerned, and where the use without due cause of the trade mark applied for would take unfair advantage of, or be detrimental to, the distinctive character or the repute of the earlier trademark”.

On 4 October 2016, the Opposition Division of the EUIPO upheld the opposition, considering that there was a likelihood of confusion (article 8.1.(b) REUTM) without entering into any assessment of whether unfair advantage was being taken of the reputation of the earlier GCB trademark or was detrimental to the distinctive nature. Subsequently, the First Board of Appeal of the EUIPO dismissed the appeal lodged by CCB, taking into account the reputation of GCB’s earlier trademark in France. Following a comparison of the signs, the First Board of Appeal considered that, in the light of the reputation of GCB’s trademark, the existing differences between the signs were not sufficient to rule out a likelihood of confusion.

CCB appealed the EUIPO decision at the General Court of the European Union (GCEU) holding that (i) it had failed to correctly assess the reputation of the earlier trademark in all the services claimed; and (ii) failed to have regard to the figurative nature of the signs at issue. It analyzed those signs as if they were word signs, thus incorrectly assessing the likelihood of confusion. Nonetheless, the GCEU also considered that there was a likelihood of confusion and dismissed the appeal.

CCB persevered and decided to file a cassation appeal at the CJEU alleging, among other grounds, that the GCEU should not have taken into account the reputation of GCB’s mark when assessing the similarity between the signs. And in fact, the CJEU held that “It is therefore incorrect in law to assess the similarity of the signs at issue in the light of the reputation of the earlier mark.” In short, the CJEU concluded erroneously that both the distinctive character and the reputation of a trademark are relevant components of any comparative analysis of conflicting signs, However, this is not correct. The reputation of an earlier mark is not relevant to a comparative analysis which, based on an overall examination of the signs, should be threefold, namely from a visual, phonetic and conceptual perspective. For the CJEU, the greater or lesser degree of distinctiveness or reputation of the earlier trademark could be relevant in determining whether or not there is a likelihood of confusion, yet not, as we have said, when determining the similarities and differences between the signs.

So what are we to conclude? The prohibition on registration, pursuant to article 8.1.(b) of the REUTM, requires the opponent to demonstrate the existence of similarity between the signs in order to invoke a likelihood of confusion. Having proved the similarity, the existence of a considerable degree of recognition of the earlier mark by the consumer public at whom the goods and /or services were aimed could be useful when proving the existence of a likelihood of confusion, that is, it might make it easier for consumers to associate the conflicting signs or to consider that the goods and services they covered had the same business origin.

Conversely, if there is a sufficient degree of similarity between the signs, even if they protect different goods and services, the trademark with a reputation will continue to merit reinforced legal protection, if the trademark holder can prove that should the conflicting trademark application be registered, it will be taking unfair advantage of their mark’s reputation, or it will be detrimental to the distinctive character of their earlier mark.

Garrigues Intellectual Property Department