The Spanish Patents and Trademarks Office (OEPM) has declared the Arturo’s trademark (related to food and accommodation services) invalid, after finding the application was filed in bad faith. The agency observed that the only reason for applying for registration of the trademark was to seek a ransom from the party the applicant believed to be its lawful owner, namely Arturo’s the famous Venezuelan fried chicken brand.

In the trademark world, the saying “he who strikes first strikes twice” takes on a concerning meaning: some parties are quick to register another person’s name to block the genuine owner. There is nothing new about this occurrence, known as trademark squatting, although it continues to be a silent threat for companies engaged in the international expansion of their businesses.

The most straightforward sequence is where a third party — completely unrelated to the lawful trademark — registers in a country the distinctive sign of another, usually relatively well-known, company, without any genuine intention of using it. The aim is usually to force them into negotiating: either you buy the registration or you are left outside.

The victim of trademark squatting in this case was Arturo’s, the famous Venezuelan fried chicken chain, created in 1986, with more than 70 restaurants in Venezuela and an international presence in countries including Mexico, the U.S., Costa Rica and Chile; although not in Spain. The fact of Arturo’s not having any activity in Spain did not prevent the OEPM from refusing the application for the trademark with the same name unrelated to the original chain, because it considered the application was being made in bad faith.

The Arturo’s case: squatting Spanish style

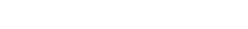

In 2020, someone decided to register the Arturo’s trademark (for food and accommodation services) in Spain. The problem is the name is not new and has been associated for years with an international fried chicken chain present in several countries and with previous registrations, including Spain.

The lawful owner, BDT Investments Inc., decided to apply to OEPM for the registration to be held invalid, on the ground of bad faith. The submitted elements of proof notably included a total lack of use of the sign by the applicant, and in particular, an email in which it offered to sell the trademark for up to €28,000.

The core of the dispute is clear: earlier valid identical registrations (graphic trademark and word mark), applicable to the same services, and an applicant that neither used the trademark nor could prove a credible commercial logic.

In May 2025, the OEPM accepted BDT’s arguments, held that the objective factors likely to indicate bad faith had been proven, and rendered the registration null and void. The applicant could not prove a lawful interest, and the attempt to monetize another person’s trademark with a direct offer to sell the registration for €10,000 — which later climbed to €28,000 without any plausible explanation — was the decisive factor in the end.

Key legal arguments

The OEPM ruled to uphold the invalidation on the ground of bad faith (art. 51.1.b) of Law 17/2001) after determining that the applicant acted with dishonest intent by trying to prevent lawful use of the trademark without aiming to make genuine use of it.

That entity refused the trademark in light of article 51(1)(b) of the Trademarks Law, based on an interpretation completely aligned with the case law of the Court of Justice of the European Union:

- Chronology of events: subsequent registration and attempt to block.

- Likely knowledge of earlier trademarks including foreign trademarks.

- Similar sign and sectors (food).

- Absence of a lawful commercial purpose.

- Speculative offer to sell for no economic reason.

The OEPM made it clear that proof of these objective factors overturns the presumption that the applicant made the registration in good faith, which means that, if there is a suspicion of bad faith in the application it is the challenged owner that must prove they did not act in bad faith. In this case, as might be expected, they could not prove this to be the case.

Significance of this decision

The Arturo’s case shows how the OEPM can decide trademark expiry and invalidity cases administratively and clarifies the main criteria for finding bad faith in trademark registration applications. This proceeding was one of the first where this organization used its direct power to declare applications invalid on the ground of bad faith since it acquired this right in January 2023. This shortens time periods, reduces costs and brings the OEPM’s Spanish practice closer to settled EU case law which already recognized bad faith as a ground for invalidity.

The decision underlines that bad faith is not simply copying a trademark to use it without having a lawful right to do so. It is also present in registering the trademark for the sole purpose of preventing the lawful owner using it or only to resell it. In short, these are all considered to be actions contrary to fair commercial practices which can be canceled administratively without needing to take the case to the courts.

How to protect from squatting

From a prevention standpoint it is recommendable to:

- Register before operating on a market, by reference to the company’s short and medium term expansion plans.

- Set up trademark watch services to identify conflictive applications early on.

- Wherever possible, diversify registrations by including, for example, transliterations of the main trademark in places where the Roman alphabet is not used; in China, for example.

As reactive measures:

- If the trademark has not yet been granted, the option of filing an objection within the allocated time limit may be assessed. This is the fastest route without a doubt, because it cuts off the problem even before the trademark applied for in bad faith has even had access to the register.

- If the trademark is already registered, there is nothing to prevent applying for administrative invalidation on the ground of bad faith (or expiry due to lack of use if no genuine use has taken place in more than 5 years – art. 39 Trademarks Law -).

It is always important to collect any items of proof that will help support the case that the application was made in bad faith. There is no magic formula and the type of proof will depend on the circumstances of each case. Having said that, the following types of evidence will be very useful:

- Proof relating to protection of the trademark in other countries and, if possible, on its reputation. This can be obtained from lists of registrations, decisions recognizing the trademark’s reputation, affidavits from organizations in the sector, surveys and so on.

- Documents evidencing that the trademark applicant knew that the earlier registration existed. In this case, the similarity of certain graphic or stylistic elements of the trademarks can be a solid indicator of bad faith. It may be likely that two trademarks are similar by chance, but it is not believable that chance is also behind the use of similar logos or graphics. In this case, the similarity between the signs leaves little room for doubt:

- Correspondence providing proof of an attempt to sell or block, such as emails or declarations containing economic offers by the applicant in bad faith.

Conclusion: a global threat with a local focus against which lawful owners can defend themselves

Trademark squatting knows no borders although every jurisdiction has its own specific features. In Spain, the Arturo’s case is seen as good news for lawful owners, anyone who builds trademarks with consistency and genuine intent, and brings ill wind for anyone speculating with empty registrations.

The case reinforces the bad faith standard under article 51(1)(b) of the Trademarks Law, applying the CJEU’s criteria: taking all factors into account (chronology of events, similarity of signs and services, knowledge —even if presumed — of earlier uses, lack of commercial logic behind the registration and request for a payment), and accepting that foreign rights can operate as relevant factors (CP13, Ann Taylor, T‑3/18 and T‑4/18), even if the third party’s Spanish trademarks subsequently expire.

Braulio Robles

Intellectual Property Department