A judgment from the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) clarifies the scope of third-party use of trademarks, taking into account the changes introduced in the European Directive on trademarks.

On January 11, 2024, the CJEU ruled on the preliminary question (Case C-361/22) raised by the Spanish Supreme Court in the proceedings between Inditex and Buongiorno Myalert, S.A. regarding the use of the ZARA trademark. We will examine the impact of the ruling in cases involving the use of third-party trademarks.

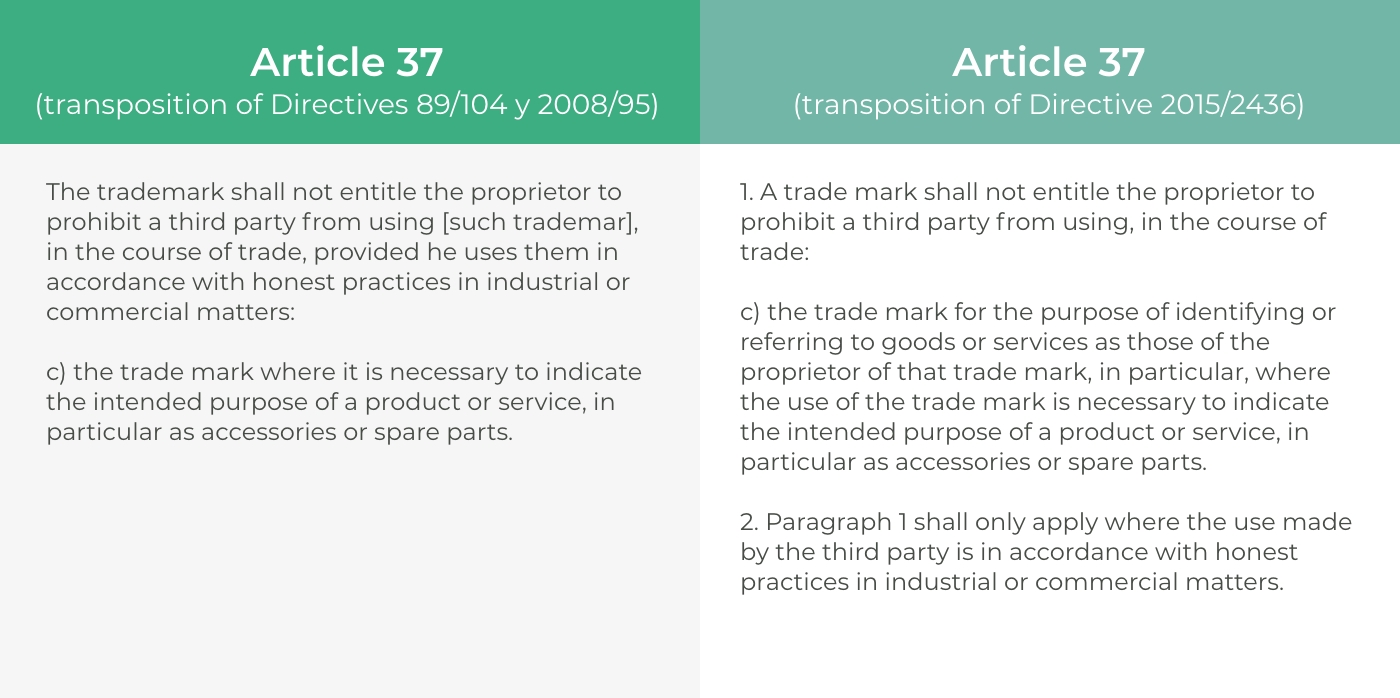

Article 37 of the Spanish Trademark Law 17/2001 states that the owner of a Spanish trademark cannot prevent a third party from using the trademark in economic transactions, among other situations, when such use (i) “is necessary to indicate the intended purpose of a product or service, in particular as accessories or spare parts” and (ii) “is in accordance with honest practices in industrial or commercial matters.” This wording corresponds to the transposition of Directive 2015/2436 of December 16.

The aforementioned article, in its previous version (corresponding to the transposition of Directive 89/104 of December 21 and Directive 2008/95 of October 22), established the limitation in a substantially different manner, as follows: “The trade mark shall not entitle the proprietor to prohibit a third party from using [such trademark], in the course of trade, provided he uses them in accordance with honest practices in industrial or commercial matters, where it is necessary to indicate the intended purpose of a product or service , in particular as accessories or spare parts.” The CJEU clarified the scope between the two versions at the request of the Supreme Court.

Buongiorno was an internet and mobile telephone network provider that, in 2010, launched an advertising campaign for a paid subscription to a messaging service for receiving content via SMS. Subscribing to the service allowed participation in a price draw where one of the prizes was a ‘ZARA gift card’ worth one thousand euros; for prize identification, Buongiorno reproduced the ZARA trademark within a rectangle resembling a gift card.

Inditex filed a lawsuit against Buongiorno for trademark infringement and, subsidiarily, for the commission of unfair competition acts. Buongiorno replied to the lawsuit by arguing that the specific use of the ZARA trademark was not intended as a trademark use but rather as “referential” use to indicate the nature of the prize. They claimed the lawfulness of such use under the limitations specified in Article 37 of the Trademark Law, both in its original version and as modified by Directive 2015/2436.

The Commercial Court No. 2 of Madrid dismissed the lawsuit (Judgment 87/2016, March 15). This decision was upheld by the Provincial Court of Madrid (Judgment 289/2018, May 18), ruling that Buongiorno did not commit any infringement or unfair act. Instead, they made a descriptive use of the trademark that did not harm its reputation or involve an undue exploitation of its reputation. Therefore, according to our courts, Buongiorno’s use of the ZARA trademark was deemed justified as it was necessary for prize identification, falling within the legal limitations provided for in trademark law.

After Inditex filed an extraordinary appeal for procedural infringement and a cassation appeal, the Supreme Court dismissed both (Judgment 725/2021, October 26). However, later in May 2022, the Supreme Court itself annulled the mentioned decision and referred a preliminary question to the CJEU, suspending the proceedings until the question was resolved. The question focused on clarifying the scope of the mentioned limitation.

According to the Supreme Court, the current wording of Article 37 of the Trademark Law mentions a general conduct, namely, “identifying or referring to goods or services as those of the proprietor of that trade mark […] making reference to them,” followed by the phrase “in particular.” Subsequently, a more specific conduct is mentioned, namely, “where the use of the trademark is necessary to indicate the intended purpose of a product or service, in particular as accessories or spare parts”.

However, since the previous wording only referred to the more specific conduct, the Supreme Court doubted whether the initial wording also implicitly included the general conduct or if the scope of “referential” uses was expanded by Directive 2015/2436. In the latter case, these referential uses would not be covered by the original wording of Article 37 and, consequently, would not be lawful uses.

The ruling delivered by the CJEU on January 11 clarifies that the use that could limit the effects of the trademark under the 2008 Directive became one of the cases of lawful use that the trademark owner cannot oppose under the 2015 Directive. In other words, the scope of the initial wording of Article 37 was more limited, as it only referred to the use, in economic activity, of the trademark when necessary to indicate the intended purpose of a product or service.

This is in line with the Opinion of Advocate General Maciej Szpunar (published by the CJEU on September 7, 2023), in which the advocate clarified that the legislative purpose of “referential use,” understood as a limit to the trademark right, is to “to enable providers of goods or services, which are supplementary to the goods or services offered by a trade mark proprietor, to use that mark in order to inform the public of the practical link between their goods or services and those of the proprietor of the mark.”

Let’s imagine that we market coffee capsules compatible with Nespresso® or Dolce Gusto® coffee makers; in that case, it is necessary to make reference to the trademark so that the consumer knows they can use them in those coffee makers. Therefore, trademark owners cannot prevent their use, as it is understood that there is a practical link, provided it is done in accordance with honest practices.

Accordingly, under the previous wording of Article 37, there needed to be a practical link between the third party’s products or services using the foreign trademark and the products or services of the trademark owner.

Therefore, Buongiorno could not rely on the limitation to the rights of the trademark owner introduced by Article 14 of Directive 2015/2436 because its use of the ZARA trademark was not covered by Article 6 of Directive 2008/95, applicable at the time of the campaign, unless it could be considered as necessary to indicate the intended of a product or service of the third party.

It will now be the Supreme Court’s task to determine whether, through the advertising campaign in question, Buongiorno effectively made use of the ZARA trademark and, if so, to assess, in light of the wording of Article 37 in force at the time of the events, that is, in accordance with the transposition of Directive 2008/95, whether that use was necessary to indicate the intended purpose of a service offered by Buongiorno and, if applicable, whether it was done in accordance with honest practices in industrial or commercial matters.

Consequently, we will have to wait a little longer to see the resolution that puts an end to a controversy that began over thirteen years ago. What we can conclude is that the current wording of Article 37 of the Trademark Law expands the scenarios in which one can use another’s trademark lawfully (without the authorization of the registered owner) compared to the previous wording of the said article.

Isabel Pascual de Quinto Santos-Suárez