The sale of the NFT ‘Everydays – The First 5000 Days’ by the digital artist Beeple for $69 million will go down in history, not only as the most costly digital artwork ever and the third most expensive purchase of a living artist’s work to date, but also for shining the global spotlight on nonfungible tokens (NFT), a blockchain-based technology that has managed to turn abundance into scarcity, or even something completely unique, thus revolutionizing the concept of digital (and intellectual ) property.

NFTs, also known as crypto collectibles, have managed to emulate physical ownership in the digital world through the issue of authenticity certificates based on blockchain technology. What actually happens is that the digital file is joined to a unique hash code and indelibly recorded in a block chain, such as, for example Ethereum. In the best tradition of art collectors, there is nothing to prevent the owner of ‘Everydays – The First 5000 Days’ from putting it up for sale again, for which purpose a new link in the chain will need to be created in order to reflect this new transaction. This is one of the main differences between traditional art collecting and crypto art collecting, as blockchain means that new information can be added, but without deleting what has already been recorded. In this way there is total traceability of works, which means one headache less for art historians.

‘Everydays – The First 5000 Days Token ID 40913’ as a unique work

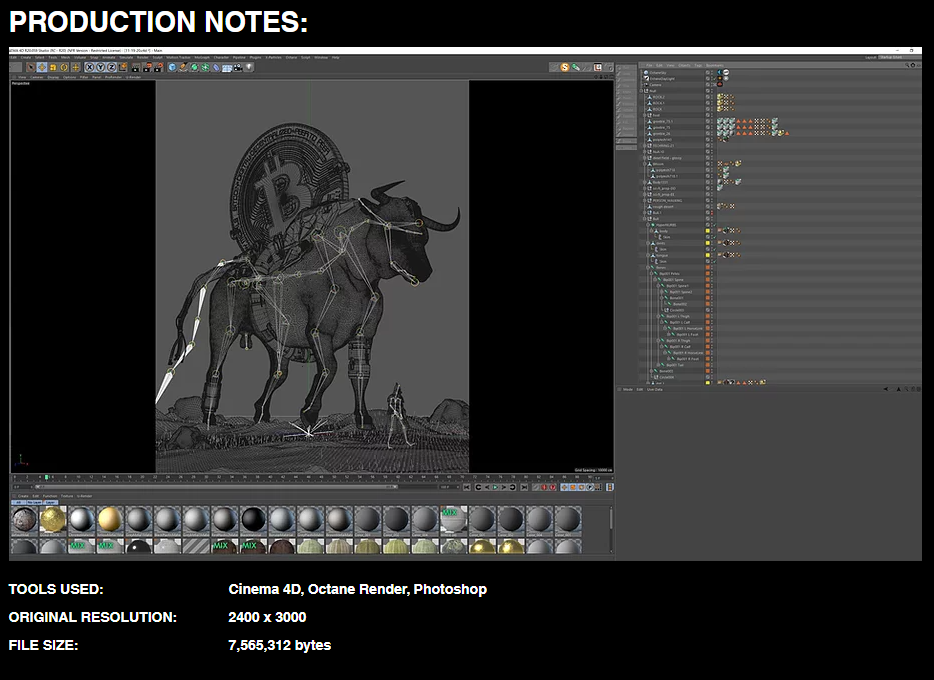

In the case of Beeple, the work auctioned by Christie’s consisted of an NFT associated with the original .jpeg file of 21.069 x 21.069 pixels created by the artist. As the website of the renowned auction house indicates, the .jpeg file identified by Token ID 40913 is “a unique work”. And that is what it is, however difficult it may be to accept that digital files can also be “unique” and exclusive. We all know the difference between an original canvas hanging on a museum wall and the printed images in the exhibition catalogs we buy as a memento of our visit. However, it can be difficult to understand the difference between two .jpeg files that reproduce the exact same image. But the fact is that there can indeed be a unique original file, and Beeple himself explains this on his website, where he includes detailed information on the production of his digital works and the successive transformations and progressions of each digital file:

© www.beeple-crap.com

We can ascertain the date the file was created, its different phases, development, the tools and effects used… in short, the artist’s entire creative process up to completion of the work. This is what makes it unique and irreplaceable. And this, in turn, helps digital art reclaim that lost aura of uniqueness and basically explains why someone is prepared to pay $69 million for a promise of authenticity, something within the reach of a mere handful of people.

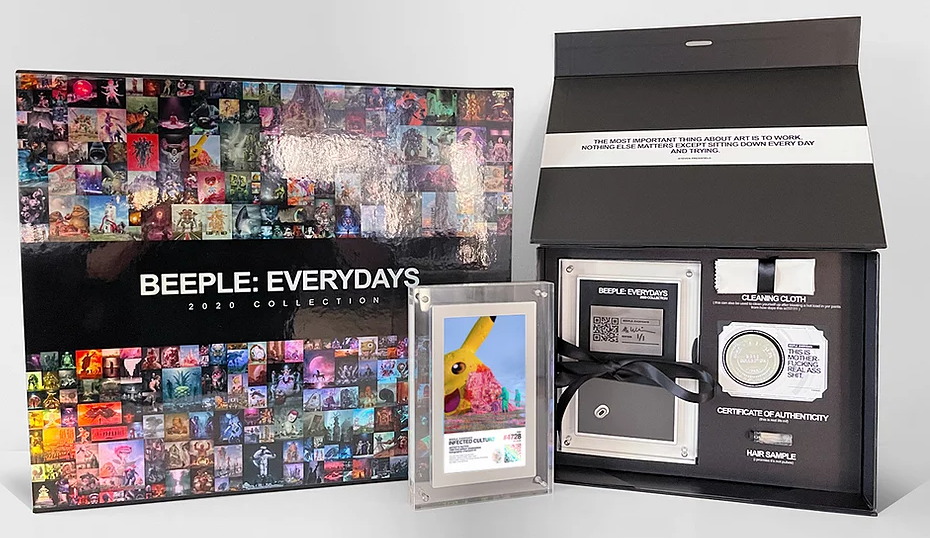

Beeple knows that the romantic charm of the original digital file is a difficult concept to grasp and therefore created a specific pack for collectors including both the NFT in blockchain attesting to ownership of the work and a physical token comprising a digital screen showing the work, the token ID and a QR code that redirects to the artist’s webpage:

© www.beeple-crap.com

Having been assured of the ownership of the digital asset, an infinite number of questions arise from the perspective of intellectual property.

The sale of the NFT for an original digital file (for example, .jpeg, .mp3…) does not imply assignment of intellectual property rights in the work.

The creator of an artwork is, by default, the holder of all the intellectual property rights in that work, including both moral and property rights. In the case in question, the sale of the .jpeg ‘Everydays – The First 5000 Days’ by Beeple implies that he is parting with the original file, the equivalent of physical format in the analog world, but not with the intellectual property rights in his work. That is, the $69 million paid by the purchaser – identified by the pseudonym Metakovan – does not include assignment of the artist’s intellectual property rights.

The dichotomy between the corpus mysticum (intangible intellectual creation) and the corpus mechanicum (analog or digital format in which the intellectual creation is materialized) is also applicable to digital art. Seeking a similar case in the analog world, the judgment of the Madrid Provincial Appellate Court no. 13/2010 of January 22, 2010 held that purchase of a sculpture does not imply assignment of the author’s intellectual property rights:

“The purchase of a work of art does not imply acquisition of the author’s right or their faculties in respect of the work. The purchaser of a painting or a sculpture cannot reproduce it or distribute copies of it, nor may they publicly display the work or transform it or authorize its transformation “.

That is, although a digital artist sells a digital file (corpus mechanicum), which is an embodiment of his or her intellectual creation (corpus mysticum), in principle, the artist retains all the intellectual property rights in that creation.

Quite another issue are the difficulties that can arise in cases where the tokenized work was created in the context of an employment relation or where it forms part of a work created in collaboration with various authors. In these cases, the task of analyzing ownership of the intellectual property rights becomes more complex, and will need to be determined case by case.

Crypto creators (or crypto owners) may also assign their intellectual property rights

The fact that assignment of intellectual property rights in a work does not go hand in hand with the sale of the physical (or digital) format does not mean that they cannot be tied together. They can, although certain limitations need to be considered, depending on the country. In Spain (and throughout the European Union), intellectual property rights comprise both moral and property rights, and only the latter can be assigned. That is, however much they may wish to, authors cannot assign faculties such as the right to be recognized as authors, the right to the integrity of their work, or the right to publish the work. Nonetheless, in countries such as United States, it is possible to waive moral rights in a work, thus demystifying intellectual property to a certain extent, to the point where it can be likened to any other type of property.

Except for these limitations, the parties can negotiate the terms of the assignment or license. For example, it could be agreed to assign all the rights in the work, exclusively, and worldwide, for a maximum period of the duration of those rights, which aside from obvious differences, likens the assignment to a traditional sale agreement. Or conversely, a nonexclusive license could be granted, limited to one territory, specific period of time or specific medium, which would certainly considerably limit the faculties of the licensee.

For example, Javier Arrés, a cryptoart pioneer in Spain, markets his original gif-arts and series through the platform MakersPlace, with a noncommercial license for use:

“You are buying a limited edition digital creation signed by its creator. Following your purchase, you will be entitled to use, distribute and show the creation for noncommercial purposes. Given that you own this unique creation, you can also resell the same noncommercial rights for use of the work in a secondary market, or even directly through MakersPlace”.

Given the variety of options available, the terms of each sale or authorization must be analyzed on a case-by-case basis in order to determine the terms for exploitation of the work being purchased, and whether or not this includes entitlement to exploit the asset.

Looking ahead…

Beeple’s sale has shone the spotlight on NFT, a technology that has been in use since 2017 (see CryptoPunks) and that features in a number of initiatives that go well beyond the confines of art collecting. An example of this phenomenon is Top Shot Moments, which allows you to collect top moments of NBA games in the form of digital packs, or Real Madrid having recently joined the Sorare platform, where you can collect NFT of the team players to participate in their Fantasy League.

The possibilities available in the world of collectibles are infinite and are directly changing both our concept of “ownership” and the intermediary mechanisms and traceability of digital creations, heralding new markets for crypto assets that we can scarcely imagine at present. And at this point I can’t help but ask … what would Walter Benjamin think of all this?

Cristina Mesa Sánchez

Intellectual Property Department