Although the AI Act (Regulation 2024/1689) does not regulate copyright, it does recognize the existing tension between technology providers and content creators. Seeking a balance between these two forces, it provides for the implementation of opt-out mechanisms allowing the owners of protected works to stop them being used to train AI models, while also allowing them to require suppliers to disclose the sources they have used. Compliance will start to apply on August 2, 2025, so now is the time to make sure that general-purpose AI model providers – including generative AI models – are ready to comply.

Legal déjà-vu: every leap in technology shakes the copyright rules

Every technological breakthrough pulls at the foundations of copyright rules. The Betamax REC button unleashed the famous Sony v Universal case and opened the door to private copying, which allowed users to record programs retransmitted on television at home to watch them later; Napster converted music into files that could change hands in seconds and triggered the creation of digital licenses; and even online search engines were questioned until the quotation exception and the CJEU case law allowed their snippets.

That tension has now moved to generative AI. Every week we see new legal action brought in relation to newspapers, photographs or opinion articles to decry the mass ingestion of their contents to train models without authorization or compensation.

Opt-out mechanisms: the right to say “don’t use me to train”

A key element of the European copyright legislation is the opt-out mechanism introduced by Directive 2019/790 on copyright and related rights in the Digital Single Market. It is contained in article 4(3) which provides an exemption allowing text or data mining (training basis) on protected contents, if they are lawfully accessible, unless the owner has reserved their rights to exclude their contents from these activities. In other words, content creators or other rightholders have the right to object to their work being read, analyzed, extracted or reproduced to train AI models (except for a purely scientific purpose).

The AI Act has included this opt-out mechanism and made it an express obligation for AI developers. In article 53.1(c) it requires providers to put in place a policy to identify and comply with any reservations of rights made by the owners of protected works. In other words, Gen AI systems must be designed to identify and accept any “do not use” instructions that rightholders have associated with their contents. The AI Act says that state-of-the-art technology must be used for this task, implying an expectation for the industry itself to develop effective technical tools (metadata trackers, web crawlers obeying the instructions in robots.txt, digital identifiers, among others) to filter opted-out contents.

The Kneschke v LAION case at a Hamburg court (2024) illustrates the practical issues. In this case, it was considered that a clear provision in the website’s terms and conditions (prohibiting scraping by bots, for example) is sufficient to consider that a binding opt-out has been made, without needing machine readable format or a robots.txt file. The judgment has been appealed, although it serves as a warning because some courts could recognize a reservation of rights expressed in natural language, even though the industry clearly prefers the adoption of machine-to-machine communication standards.

This obligation, moreover, is not restricted to providers established in the EU, and applies instead to every provider introducing a model into the EU, regardless of where the training or compilation of the dataset took place. The aim? To avoid competitive advantages based on training models in countries with more relaxed rules.

Transparency obligations: showing (part of) the dataset

Secondly, the AI Act imposes transparency obligations on providers of GPAI models to shed light on the material actually used to train their models and by doing so be able to verify whether they have obeyed the opt-out instructions given by rightholders.

Article 53.1(d) of the AI Act requires providers to draw up and make publicly available a sufficiently detailed summary about the content used to train the GPAI model, according to a template provided by the AI Office. This summary must include the main content sources used. The aim is that, without disclosing trade secrets – which include the setup of the dataset – or entering into technical details, the summary should provide an overview to parties with legitimate interests to make them aware of the type of contents that have been used.

Exceptions to this obligation? Very few. Basically, the developers of models for non-professional or scientific research purposes. The AI Act does, however, allow simplified ways of compliance for small and medium-sized companies.

The Code of Practice that never arrives …

That is the theory, but practical implementation is far from straightforward. The AI Act provides for the preparation of a code of practice to facilitate compliance with the obligations of GPAI model providers which will start to apply on August 2, 2025. The code should have been approved on May 2, 2025 although at this point there is no foreseeable date for its final approval.

In relation to copyright, the third draft of the Code of Practice (published on March 11, 2025) sets out the following commitments:

- To draw up, keep up-to-date and implement a policy (single document) that will explain how the GPAI model provider complies with EU copyright legislation and assigns responsibilities within its organization.

- To carry out responsible web scraping, by ensuring that when crawling the web, only lawfully accessible contents are used, and they do not circumvent paywalls or anticopying measures, and they exclude piracy domains recognized by courts or authorities.

- To identify and comply with opt-out mechanisms, using robots.txt files or other standard metadata, collaborate with widely adopted standards and provide information on their crawlers.

- Where third parties’ datasets are used, to try to verify that they are also compiled with respect for reservations of rights.

- To mitigate the risk of a model memorizing copyrighted works and repeatedly producing copyright-infringing outputs (i.e. overfitting).

- To designate a visible point of contact for communication and an electronic procedure for rightholders to report non-compliance.

This is simply a draft, however. The debate is ongoing and there is increasing skepticism as to whether the final version will be published in 2025, which is fueling requests in the industry to postpone the implementation of the AI Act’s obligations due to the absence of clear guidelines.

The OECD’s (voluntary) compass

In February 2025, the OECD published a report entitled Intellectual Property Issues in AI Trained on Scraped Data, which outlines the creation of a voluntary code of conduct in relation to scraping and copyright for AI developers. While not mandatory, it is an extremely useful point of reference from technical and policy standpoints. After carrying out a general analysis with particular attention to the European exception to data mining and to the U.S. fair use doctrine, the report concludes that uncertainty over its scope is today the main legislative obstacle for the development of generative AI.

In this landscape, the OECD recommends the adoption of voluntary codes of conduct frameworks based on three approaches:

- Transparency in the data chain, by disclosing the sources and preserving metadata that will allow rightholders to track unauthorized uses.

- Adoption of standardized opt-out mechanisms, involving a machine-readable label (extension of txt with the ai-policy:disallow instruction or embedded metadata), and the creation of a public register for reservations of rights.

- Solutions involving collective rights and standard contract terms that will facilitate swift agreements between creators and AI firms where an opt-out is not sought, in other words, in cases where the owner does not want to exclude the content and prefers to receive an amount of compensation for its use.

The OECD guidelines are not binding but will doubtless be a main reference point on policy for regulators. While waiting for the Code of Practice to be strengthened, and in the absence of a postponement, these guidelines can serve as a guide for compliance with the obligations that the AI Act imposes on providers of GPAI models.

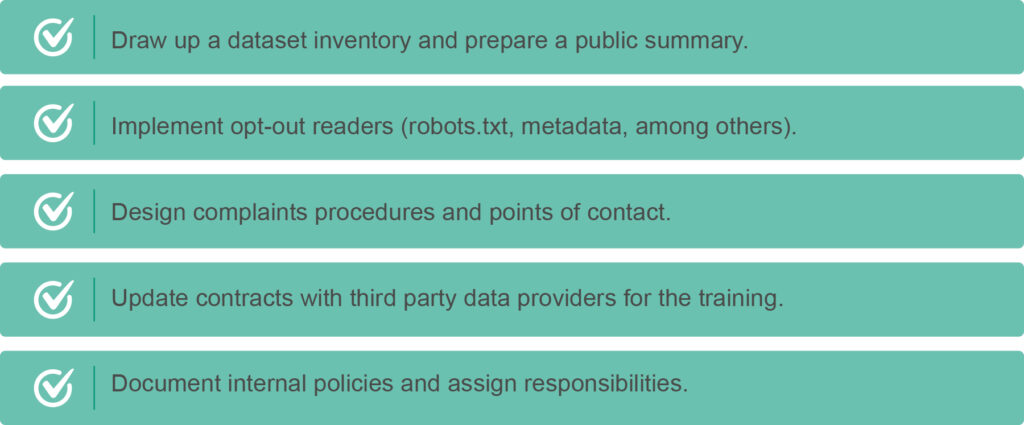

Immediate checklist for GPAI providers

To conclude, GPAI model providers must:

Conclusion

There is less than a month left. Failure to act and waiting are no longer options. GPAI model providers must comply with the opt-out and transparency mechanisms required by the AI Act to avoid penalties, and especially, to build trust with content owners and users. There are two ways of looking at compliance with AI legislation: as a burden or as a competitive edge. The challenge now is not to question the provisions of the AI Act but to decide how we are to comply with its obligations.